Weekly Market Commentary: Treasuries: Who's Buying And Why It Matters

February 20, 2024

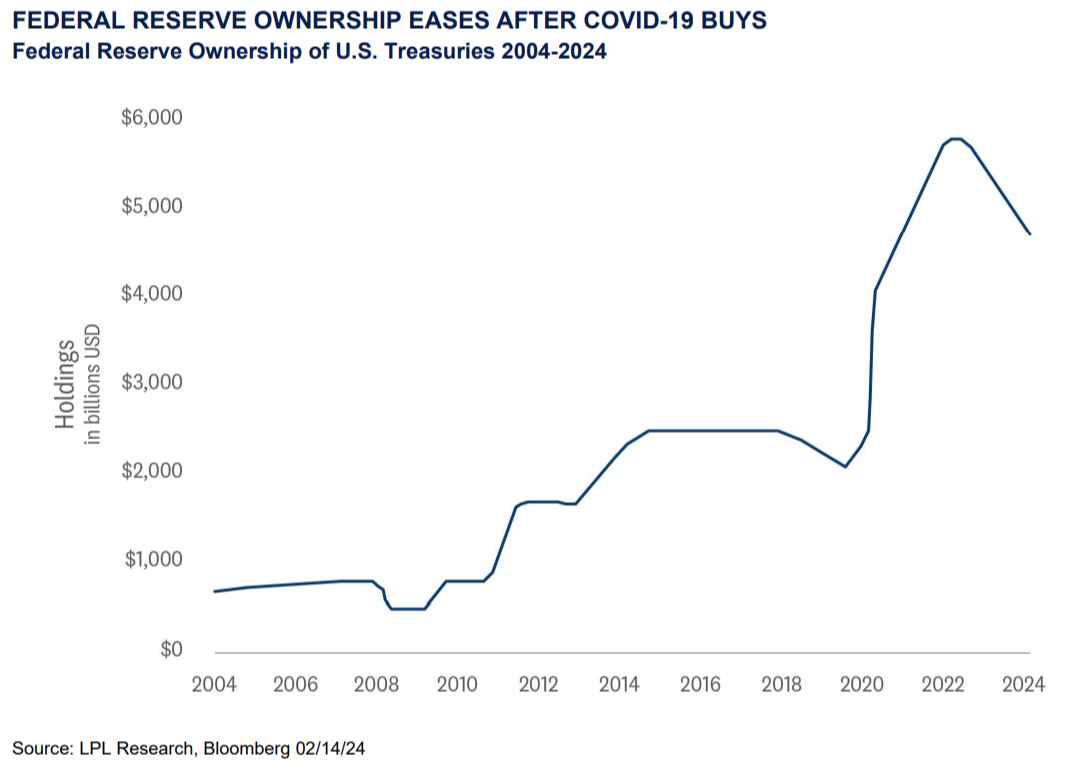

As the Federal Reserve (Fed) continues with its Quantitative Tightening (QT) program, questions abound regarding the Treasury Department’s expanding funding needs. The QT program is designed to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet — now $7.7 trillion down from $9 trillion — after Treasury notes (mostly) were bought after economic concerns intensified during the COVID-19-related pandemic. Households and, perhaps surprisingly, foreign investors have been buyers recently, and with the amount of Treasury supply coming to market, both will need to keep buying.

According to recent data from the congressional budget office (CBO), total Treasury debt held by the public is expected to grow to over $46 trillion by 2033. The primary reason for the increase in expected debt issuance is an increase in spending. Per the CBO, the U.S. government is expected to run sizable deficits over the next decade in the tune of 5%–7% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) each year. So, to fund those deficits, the Treasury Department needs to issue debt. And Treasury plans to issue a lot of debt. And, thus, the Treasury needs buyers.

At this point, the Fed is no longer a buyer of Treasuries. Pension funds, mutual funds, retail portfolios, institutional portfolios, and an assortment of exchange traded funds have been important domestic buyers. Foreign buyers continue to remain active buyers participating in Treasury auctions, but global central banks have not been as active in Treasury auctions as they once were.

With the national debt standing at $34.23 trillion and expected to grow, U.S. Treasury sales are the key to paying the carrying costs. Each auction is heavily monitored by fixed income and equity markets alike to see where the yield settles, as higher yields have a more negative effect on the overall economy.

THE FED AS BUYER OF BONDS IN PERIODS OF ECONOMIC STRESS

The Fed has a history of stepping into the Treasury market during periods of economic stress, with the Great Recession (2007–2009) popularizing the term “Quantitative Easing” (QE), when the Fed purchased large portions of various Treasury instruments, called large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs). The Fed’s balance sheet expanded by $3.5 trillion during late 2007–2013, as the Fed continued to help bolster the economy. By the end of the recession the balance sheet was $4.5 trillion.

Resorting to an assortment of monetary measures in the Fed’s “toolbox” has been normalized and institutionalized, but a key aspect of these extraordinary purchases is that the Fed will reduce its balance sheet to pre-crisis levels, as it is currently engaged in.

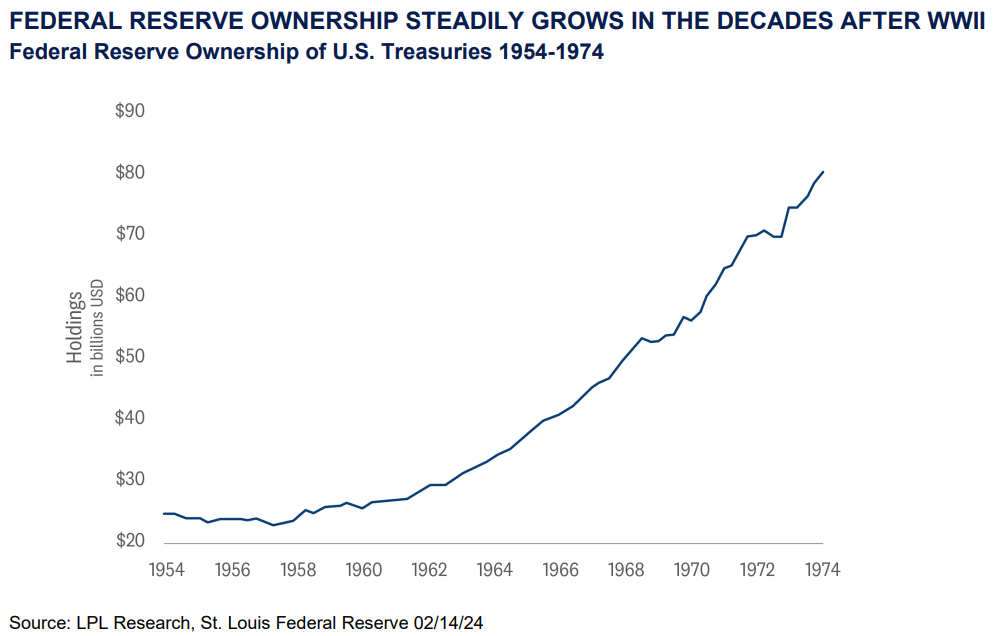

From 1941–1951, the Fed kept rates at low levels to weaken the cost of the debt incurred and subsequently kept the peg in place for six years following the end of World War II. This policy was also implemented during World War I, as well as the war’s aftermath.

But with the amount of Treasury debt that will likely come to market over the next few years (few decades?), the Treasury department will likely need to find additional demand. The current Treasury buyer base is diverse, with non-domestic buyers and the Fed serving as the largest owners of Treasury securities. However, the largest owner of Treasuries, the Fed, is shrinking its sizable balance sheet and is letting $60 billion of Treasury securities roll off each month (though debt that matures above the $60 billion threshold is currently being reinvested in Treasury securities). Currently, the Fed owns slightly more than $5 trillion in Treasury securities, or roughly 25% of issuance, but is on pace to reduce its exposure by several trillion by the end of 2024. While the Fed will likely not be able to get its balance sheet back to pre-COVID-19 levels, it likely won’t be a large buyer of Treasury securities in the near term either (unless an unforeseen macro event causes the Fed to implement quantitative easing again). So, the biggest buyer of Treasuries is likely on the sidelines for now.

GLOBAL CENTRAL BANKS AS IMPORTANT BUYERS

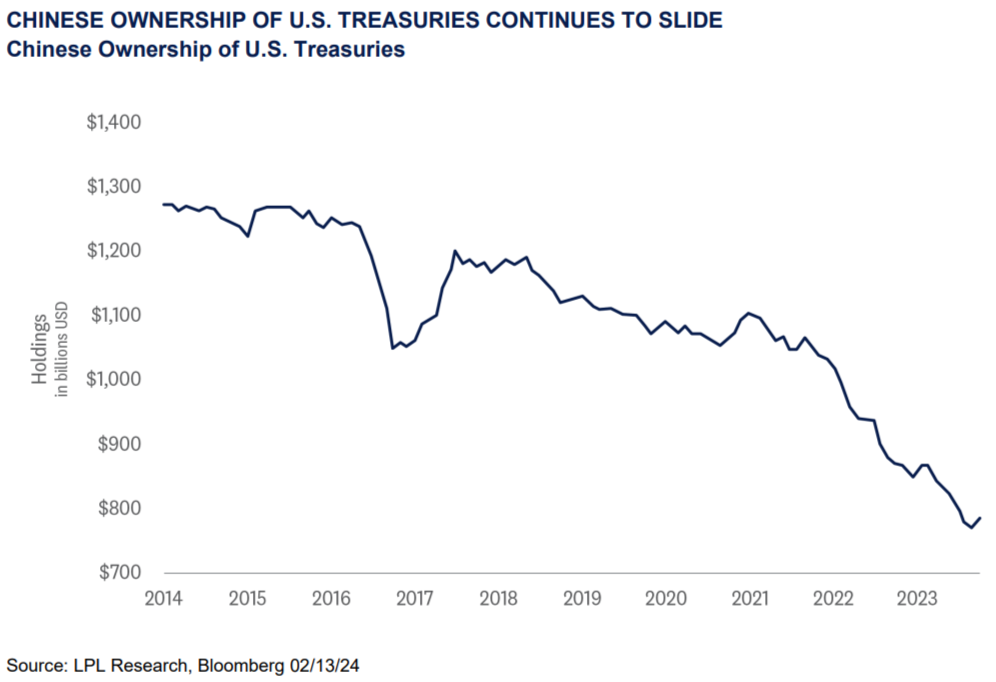

Although the Fed was the primary central bank active in the Treasury market for many decades, global central banks began to enter the market in early 2000, as the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) launched a program of heavy buying at auctions. Treasury notes provided easy and accessible liquidity for Beijing’s export profits in U.S. dollars. The purchases were of such a scale that yields moved lower on the 10-year Treasury, leading to lower mortgage rates as a consequence. There were numerous studies attributing the housing market bubble to lower mortgage rates “provided” by China.

At the end of 2006, foreign financial enterprises held nearly one-third of outstanding Treasuries, more than twice the amount on the Fed’s balance sheet. As more foreign buyers participated in the auctions, foreign holdings climbed to 40% just as the housing market was about to crash.

Following the recession, many of the global central banks, especially within emerging markets, began unwinding their positions and actively selling Treasuries.

By 2015, the reduction in global central holdings was 1.5 times the amount held by the Fed, considerably lower than during the years of strong activity in the U.S. market.

The PBOC surpassed the Bank of Japan (BOJ) as the largest buyer and holder of Treasuries, as they amassed $1.3 trillion in Treasuries. As China began transitioning away from the U.S. dollar and bilateral relations began to deteriorate, assets have leveled off at just under $800 billion.

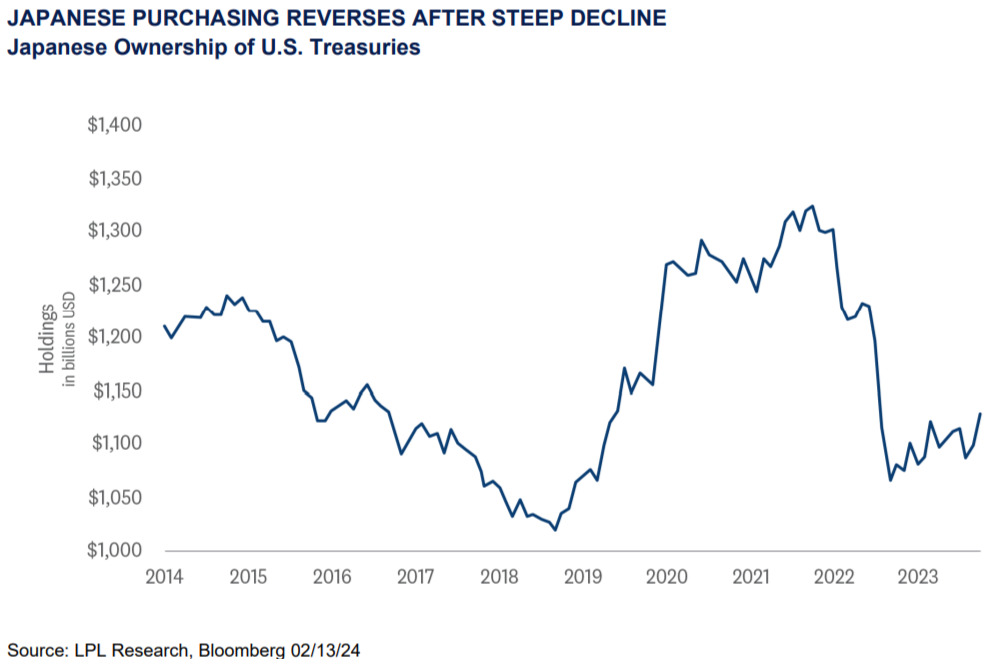

Today, the BOJ is still the largest foreign owner of Treasuries, but they have been less active over the last few years as hedging costs have climbed higher. Moreover, there are concerns that once the BOJ dismantles the Yield Curve Control (YCC) mechanism that keeps their 10-year bond within a band and proceeds with a rate hike as deflation has been defeated, the Japanese could steadily sell their U.S. holdings and repatriate funds back to Japan to take advantage of higher yields.

Many global central banks, including the PBOC, have become active buyers of gold as geopolitical concerns, in concert with an ongoing unwinding of globalization, have deterred buyers from entering recent Treasury auctions.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SUCCESSFUL TREASURY AUCTIONS

Given the outsized funding needs by the Treasury Department, auctions have become the vehicle by which investors help service the country’s expanding debt. Fortunately, the largest 10-year Treasury auction on February 7, for $42 billion, settled at a lower-than-expected yield with the bulk of the buying coming from foreign buyers. Auctions haven’t seen foreign participation this strong since February 2023.

With global central banks not as active, auctions are increasingly dependent on private buyers who are more price-sensitive than central banks. Household investors and mutual funds have both been increasing their ownership in Treasuries and will likely need to keep increasing shares to keep up with expected supply. Historically, neither has been an overly large buyer of Treasuries, but with yields at levels last seen over a decade ago, households, in particular, have been adding Treasury bills and bonds to portfolios. They will certainly need to keep adding Treasuries to portfolios to help offset supply. And with demographics shifting and baby boomers retiring, higher-yielding Treasuries will likely continue to remain attractive.

Without fiscal spending curtailed, the sale of Treasuries at a reasonable price and yield will become the barometer by which to evaluate how well the U.S. economy and financial markets are functioning. There is apprehension regarding how long buyers — foreign and domestic — can support the U.S. with attractive yields and whether they will demand better prices with ultimately higher yields.

There is also another concern if auctions draw fewer buyers. Who then will come in to take down the Treasuries? The answer is always the same — the Fed. This would be the least acceptable option to those who demand a functioning and liquid Treasury market. Should auctions become increasingly ineffectual, it may be the crisis point which forces action to finally cut the deficit.

CONCLUSION

While a lot of attention (rightly) is focused on the amount of Treasury supply coming to market over the next few years, the primary driver of Treasury yields is still Fed policy. Our base case is that the Fed will be able to cut the fed funds rate by 1%. And after a few months of overly aggressive expectations, markets have generally re-priced to be more in line with our expectations. As such, unless inflationary pressures re-accelerate, Treasury yields could be around cycle highs, which should help with demand if the market expectation is lower yields a year from now.

Moreover, the current increase in supply will occur amid a backdrop of slowing inflation and expectations of Fed rate cuts this year. Investors might require some concessions to digest the larger issues, but the improved outlook for rates this year should attract some additional demand from the sidelines.

As such, with the economic data (so far) continuing to reflect a more resilient economy than originally expected, we think Treasury yields are likely going to stay in a trading range at least in the near term. Despite the ongoing supply discussion, we think the 10-year Treasury yield could mostly stay in the 3.75% to 4.25% range this year with risks to both the upside and downside roughly balanced.

ASSET ALLOCATION INSIGHTS

LPL’s Strategic and Tactical Asset Allocation Committee (STAAC) maintains its neutral equities stance despite the strength of the latest stock market rally that has carried the S&P 500 over the 5,000 milestone. The improved outlook for economic growth and earnings, along with relative stability in interest rates, keeps the risk-reward trade-off for stocks and bonds fairly well balanced, though upside over the balance of the year is likely to be fairly modest.

Within equities, the STAAC continues to favor a tilt toward domestic over international equities, with a preference for Japan among developed markets, and an underweight position in emerging markets (EM). The Committee also recommends a slight tilt toward large caps and growth stocks. Finally, the STAAC continues to recommend a modest overweight to fixed income, funded from cash.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. There is no assurance that the views or strategies discussed are suitable for all investors or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Any economic forecasts set forth may not develop as predicted and are subject to change.

References to markets, asset classes, and sectors are generally regarding the corresponding market index. Indexes are unmanaged statistical composites and cannot be invested into directly. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investment and do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any company names noted herein are for educational purposes only and not an indication of trading intent or a solicitation of their products or services. LPL Financial doesn’t provide research on individual equities.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, LPL Financial makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

All investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal.

US Treasuries may be considered “safe haven” investments but do carry some degree of risk including interest rate, credit, and market risk. Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P500) is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

The PE ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) is a measure of the price paid for a share relative to the annual net income or profit earned by the firm per share. It is a financial ratio used for valuation: a higher PE ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of net income, so the stock is more expensive compared to one with lower PE ratio.

Earnings per share (EPS) is the portion of a company’s profit allocated to each outstanding share of common stock. EPS serves as an indicator of a company’s profitability. Earnings per share is generally considered to be the single most important variable in determining a share’s price. It is also a major component used to calculate the price-to-earnings valuation ratio.

All index data from Bloomberg.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

Securities and advisory services offered through LPL Financial (LPL), a registered investment advisor and broker-dealer (member FINRA/SIPC). Insurance products are offered through LPL or its licensed affiliates. To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor that is not an LPL affiliate, please note LPL makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not Insured by FDIC/NCUA or Any Other Government Agency Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed Not Bank/Credit Union Deposits or Obligations May Lose Value

RES-1426900-0223 | For Public Use | Tracking # 1-05360310 (Exp. 02/24)

For a list of descriptions of the indexes referenced in this publication, please visit our website at lplresearch.com/definitions.